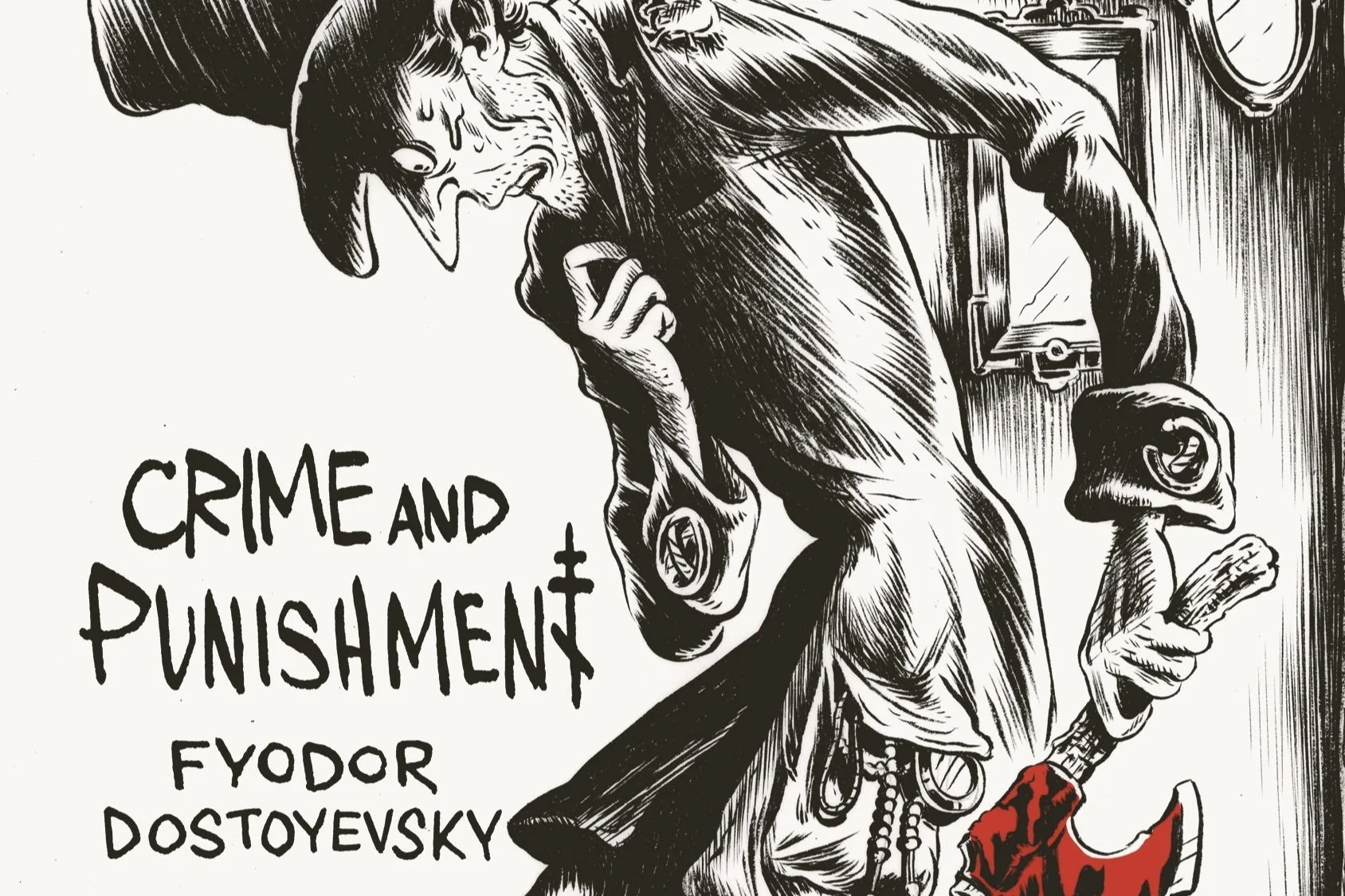

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (Review)

When I was reading, Where is God When It Hurts?, Philip Yancey described Fyodor Dostoevsky’s stint in a Siberian prison, which served as the inspiration for Crime and Punishment. It also served as the inspiration for me to read the novel. Prior to his sentence of hard labor, Dostoevsky had originally received a death sentence by firing squad. His reduced sentence came as his stood in the town square just moments from execution. This close contact with death coupled with Dostoevsky’s lonely Siberian existence caused him to scrutinize his past and think about the inner- and outer facets of his life.

In his novel, readers analyze the inner- and outer facets of the main character, Rodion Raskolnikov. Raskolnikov is a penniless, former student who plots to kill a pawnbroker for her money. His story begins in a state of pathetic sickness as readers see the sorry state of Raskolnikov’s life. Despite his shabby existence, he is not a man without friends or resources. But Raskolnikov pushes away everyone as he spirals into paranoia, and readers then watch his story unfold in horrific detail.

Undoubtedly, the details of Raskolnikov’s life make Crime and Punishment an engaging story. I am pleased I read the book. Yet I found myself in a similar posture as I have with reading other works of fiction in adulthood: “I wish I was reading this book in a classroom setting.” It’s not that I cannot appreciate a good story or explore the themes on my own, but books like Crime and Punishment call for discussion. Sadly, I’m not in a stage of life when I can allot time and structure for a book club, so I’m left to explore the themes of fiction on my own. As an incomplete substitute for a classroom discussion, the following thoughts are my takeaways from Dostoevsky’s famous novel:

I learned recently that writers in the 19th Century comfortably relied on coincidence to bring characters together despite the unlikelihood of such an event happening in real life. This is not something I remember discussing in my college literature classes. Perhaps Dostoevsky’s use of coincidences would not have bothered me if I had known or remembered the literary trend. Yet it was bothersome how often seemingly absurd coincidences proved critical to the story. Raskolnikov came to know that Lizaveta (the pawnbroker’s sister) would be in the marketplace during a happenchance walk through the market, which allowed Raskolnikov a clear path to visit Alyona Ivanovna, the pawnbroker. Then for Nikolai Dementiev—the painter—to serve as the alternative defendant seemed remarkably unlikely, and then for Razumikhin—Raskolnikov’s friend—to know about Dementiev furthered the improbable plot development. These coincidences seemed eye-roll inducing at times, which would have been helpful to know going into the book.

Raskolnikov’s dream about being a boy while he watched a mare being beat to death by the peasant Mikolka was terribly horrific. Mikolka’s declaration that he could kill it because it was his property seemed the very model of cruelty. This was the first of a few visceral and shudder-inducing dreams. Svidrigailov’s dreams after Dunya shot the revolver at him were quite awful. The mouse crawling over his body and in his clothes was unpleasant, but the nightmare of the 5-year-old harlot who mocked Svidrigailov was perhaps the worst.

I once came across the observation that humans are not rational but rationalizing. This quote came back to me often when considering Raskolnikov’s inner monologue—particularly as he contemplated killing the pawnbroker, Alyona Ivanovna. His rationalizing was core element of the book.

The assistant superintendent of the police station, Ilya Petrovich or “Gunpowder,” began yelling at Raskolnikov for showing up late according to the police summons. Raskolnikov took satisfaction at yelling back that Ilya Petrovich was disrespecting everyone by smoking a cigarette and yelling. One wonders if this satisfaction grew out of Raskolnikov’s guilt and the need to feel right in relation to his counterpart.

I do not know much about 1800s St. Petersburg, but it seems crazy that anyone would bring a nearly dead man to his apartment and drop the body in front of his family. But the event is a great setup for the religious critique of no provisions for the new widow and fatherless. Katerina Marmeladov rightly chastised the priest for offering platitudes that “God is merciful” without any food or money to provide care. It is ironic that the murderer in the story did more for the Marmeladovs than did the priest.

Raskolnikov seemed drawn to wretches he perceived worse off than himself and is repulsed by those perceived to be morally superior.

Thinking through Raskolnikov’s thinking about the murders and his confidence that he would evade the police made me think of Proverbs 26:12: “Do you see a man who is wise in his own eyes? There is more hope for a fool than for him.”

The conversation between Svidrigailov and Dunya when Svidrigailov revealed that Raskolnikov had murdered the two women was quite interesting. Dunya’s comment: “Can you save him? Can he be saved” seemed to have more of a spiritual nature rather than a temporal one.

In the epilogue, Raskolnikov was surprised at the other prisoners’ love for life. Raskolnikov at no point seemed to have any such value for life, even his own. Raskolnikov was also surprised that all the prisoners loved Sonia, though he did not know why. I wonder if her grace toward a wretch like Raskolnikov gave them hope for themselves.

There is a joyfulness at the prospect of redemption in Crime and Punishment, and joy that Raskolnikov found it despite his suffering and imprisonment. His conversations and relationship with Sofya Marmeladov make it clear that confession and suffering is necessary for redemption. Yet Dostoevsky reaffirms and concludes with the message of grace-filled hope that even the worst of people can find redemption. It is the beautiful strand that runs through the ugliness of Raskolnikov’s life.

Fittingly, The New Yorker recently published an article by David Denby who took “Literature Humanities” at Columbia University for the third time since 1961, and he once again read Crime and Punishment. This time, however, Denby had to finish the course via Zoom. He talked about the themes from the book and their applicability in a quarantine era. Raskolnikov lived in a hovel of an apartment and—despite its unpleasantness—described his inability to pull himself away from the place. This was just one point that resonated for a modern class looking at a 150-year-old book.

One student highlighted the warped appeal of Raskolnikov’s pursuit of becoming a great man and potentially achieving that end by unjust means. Another focused on a feminist critique and social justice. Denby glommed onto the larger theme of decline: “the incoherence of Petersburg, the breakdown of social ties, the drunkenness and violence.” As New York suffered from the mass spread of Covid-19 and joblessness, Denby saw how Dostoevsky described the effects of disease and joblessness in Russia, and he wondered if his own city would similarly suffer further decline. All of Denby’s observations added more depth and intrigue to Dostoevsky’s famous book, but it also saddened me to miss out on the conversations he enjoyed.

As I read about Columbia’s literature class, I thought back to If on a Winter's Night a Traveler by Italo Calvino. There was one excerpt that applied to the sadness of reading Crime and Punishment without someone to share its ideas: “...reading is a necessarily individual act, far more than writing. If we assume writing manages to go beyond the limitations of the author, it will continue to have a meaning only when it is read by a single person and pass through his mental circuits. Only the ability to be read by a given individual proves that what is written shared in the power of writing, a power based on something that goes behind the individual.” The statement is interesting and ironic because in Calvino’s book, the story’s continuous goal is for the reader to share a book with the main female character. Reading may be an individual act, but the value is much deeper when it leads to the exchange of ideas and connections between others who have similarly read (and ideally enjoyed) the same book.

I offer this statement as a professed introvert who enjoys the solitary nature of reading. Yet to keep stories to myself seems incomplete because I miss out on how the words resonated with others who read the same words. Raskolnikov’s insistence on isolation seemed to hasten his descent into madness; similarly, letting thoughts and ideas skip the refining process of exchanged ideas causes an incompleteness to our own thinking. So while I enjoyed Crime and Punishment, it would have been much richer to read it alongside others and discuss the book along the way. I’ll close by stealing Dostoevsky’s tendency toward religious themes: whether with literature or human existence, “it is not good that man should be alone.”