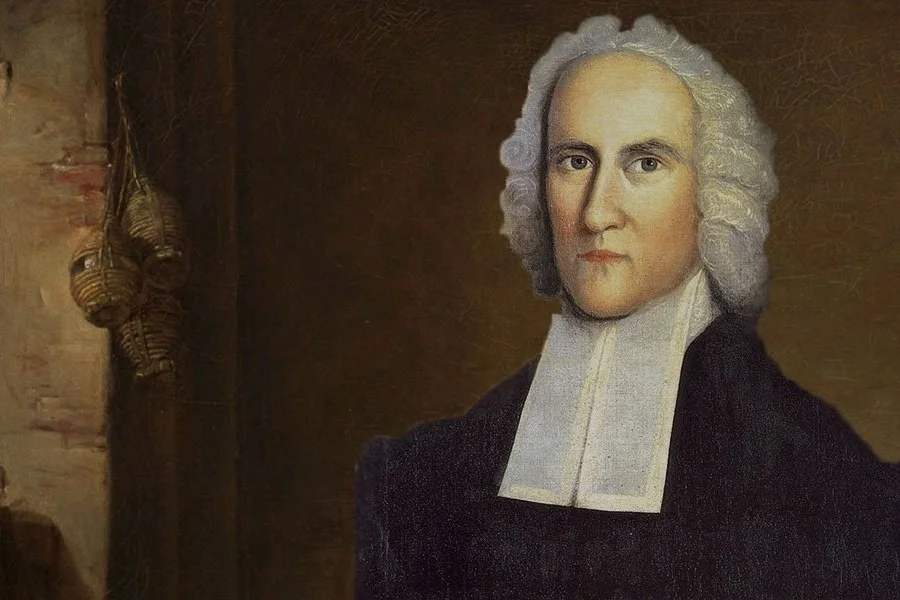

Jonathan Edwards: A Life by George Marsden (Review)

George Marsden provides one of the better introductions I have read on setting an interpretive framework for his analysis of Jonathan Edward. His effort to be objective—or fair-minded and grounded in evidence—does not mean posing as a neutral. Everyone has their own biases and interests, and Marsden acknowledged his goal to communicate his values in hopes that readers will take them into account. His expectation is that readers will either learn from or dismiss how they influence the portrayal. Such an approach is a challenging one, and Marsden executed it with aplomb. The result is a helpful book that introduces Jonathan Edwards’s theology, while effectively weaving the ideas of his major works into the story of who he was. I offer this overview with the foundation that I enjoy theology and history—particularly the foundational years of the United States. Jonathan Edwards was an impressively disciplined man, and the effect is man who may not inspire a general readership like some historical figures.

Here are some of the points I enjoyed learning during my read:

It was affirming to hear directly how Edwards wrestled with his faith and struggled with doubt on the legitimacy of his faith. Edwards grew in understanding of God’s sovereignty, which tempered the highs and lows he felt in his early life when he tried to will himself into compliance with God’s commands. Instead, he found joy in knowing God in His power and glory.

It is interesting that prophecy and logic were such elemental pieces of life in colonial America. Today, we would view the subjects as contradictory. Yet I would argue that logic is the piece we seldom dig into deeply, and prophesy—albeit more in the form of superstition and a general sense of karma—has remained a central part of individual philosophy. The result strikes me as an absence of individuals holding a cogent philosophy like the one Edwards held and Marsden was able to describe. Instead, people float from one trend to the next with no grounding in a belief system. As Marsden described it, many leaders of the day believed they could find agreement on subjects if only the premise could be agreed upon and seen clearly. Sermons flowed from syllogisms, and classical logic was essential.

Edwards’s diary reveals that his pursuit of holiness did not come easily. His great heights as a theologian emerged from times of spiritual dryness and wrestling with concepts—like God’s holiness and the concept of sinners’ damnation—that required much thought and analysis. It is a reminder that greatness in any realm does not come without sacrifice and hard work.

Jonathan Edwards took over as pastor for his grandfather, Solomon Stoddard. Stoddard had a charismatic personality, and there were some points of disagreement between Stoddard and Edwards. One was how they viewed conversion to Christianity. Stoddard thought that if people truly heard, then people would follow Christ. Edwards spent more of his early years wrestling with what it meant to follow Jesus and did not think the single moment of conversion was critical. Stoddard did not want young pastors to use notes at the lectern—perhaps an extension of his charismatic personality. Edwards was more comfortable writing his sermons and wrote out every word until late in his career. From Stoddard, however, Edwards learned to avoid having notes impede his ability to gesticulate and communicate effectively. The two pastors did agree on preaching the fear of hell in their sermons, and they saw it as a mercy. The unimaginable suffering of hell was a message that Jesus taught, so both Stoddard and Edwards did the same.

Prior to Isaac Watts’s publication of “Psalms and Hymns,” most churches adhered to the idea that praise must be verbatim to biblical text. The accompanying music was so jumbled and cacophonous that it did not seem to constitute worship.

As the the community addressed a theological controversy based on Robert Breck's positions, Marsden emphasized that this was an era of debate. Opposing sides could remain entwined on the core issues while disagreeing heartily on other issues—and do so without severing the relationship.

When George Whitfield visited America, he became the region’s first star. As Henry Stout noted, “because of America had weak established institutions, [Whitfield] was the first to demonstrate that popular opinion could counter any authority.

A biography of Edwards by his friend and fellow theologian, Samuel Hopkins, notes that those who found Edwards stiff and unsociable simply didn’t know him. Edwards committed to never speaking ill of others, so he did not banter with people as part of typical small talk. He followed the biblical advice to be slow to speak and thus only spoke when he had something to say. He also found verbal disagreements unprofitable and believed he was at his best in written discourse. That said, when discussing serious matters, he was engaging and energetic with his friends. Those who knew him found him warm and caring. The spiritual awakening in his community and the number of his parishioners that stayed under his pastoral care and sought his counsel supports that he was more than a stern and taciturn man.

Edwards and other colonial pastors struggled with the experiential and emotive elements of revival. Many individuals seemed to want the overwhelming response that some converts experienced. But being overcome with “pure raptures of joy” did not necessarily indicate real communion with Christ. The consequence of the revival was a schism and an over-correction that some pastors claimed such experiences were an indication of fraudulent Christianity. Those that critiqued the rapturous and emotional response saw the reactions as animalistic passion rather than an indication that a person was rightly following Jesus. Edwards’s conclusion was that gentleness and humility were better predictors of walking with Jesus rather than intense experiences. The schism and conflict spurred Edwards to write, “Religious Affections,” where he noted that true religion begins with great affections. This tempered response still saw value that converts could experience a rapturous response, but it must extend from the heart—the will of the person—choosing to follow Jesus in body, mind, and soul.

Jonathan Edwards’s experiences with developing theological positions and church policies show the danger of operating with a CEO/non-elder model. Without formal church leaders to serve as a sounding board and supporters for his positions, he found himself an island without the support or confidence of his congregation. This development undermined his theologically sound positions. The church suspended new memberships and ceased the sacraments. The body also pursued ouster of Edwards as pastor.

After his church ousted Edwards, the town paid for a book publication by Edwards’s cousin, Solomon Williams, to refute Edwards’s views on church membership. Marsden commented that leaders of the day thought it critical to have both reason and principle to back a position. This trait strikes me as one that American leaders no longer seem to value. It is a testament to Edwards’s spiritual maturity that he responded to his ouster with humility and a prayer that he would not be prideful and that God would instead refine him to be a more effective vessel.

It is fascinating to read the accounts of Jonathan Edwards on the missions front, as it’s a striking contrast to his pastoral reputation as a head-smart, street-fool in Northampton. His letter trail shows a savvy and awareness that suggests one of two options: (1) he was savvy as a pastor but the historical record no longer remains to support such a reputation or (2) he learned deeply from his ouster from Northampton and took more interest in the practical elements of leadership. It seems likely there was a combination of the two, but the latter—improvement and growth—is a characteristic worth admiring and celebrating, particularly given Edwards’s advanced age when he took to the mission field.

Marsden provides an admirable analysis of Edwards’s philosophy and how it both fit and opposed trends in the Scottish Enlightenment and the intellectual developments of the day. One wonders how different his lasting fame and the treatment of his writings would be had he resided in Scotland or a different European province rather than Massachusetts.

Edwards’s described the debate on reason, scientific observation, and historical reliability or testimony in a manner that is just as relevant today. It is remarkable that the same discourse is occurring all these years later.

As suggested above, I enjoyed Marsden’s book and give it a recommendation to those with an interest in theology and colonial America. It is insightful, thoughtful, and explores foundational pieces of the United States that are too often a footnote in American history. Edwards example and values lend insight into the importance of self-discipline, and I enjoyed learning more about his life and values. The book may not be in the wheelhouse of someone looking for a casual read, but Marsden’s book is certainly worthwhile for those looking for a biography with heft.